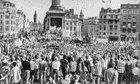

It’s three decades since the government’s attempt to ban raves radicalised an oddball coalition of dance fans, squatters and ‘new age’ travellers. What became of the protesters who tried to kill the bill?

When Harry Harrison first saw the white paper for the criminal justice and public order bill at the end of 1993, he couldn’t believe what he was reading. Harrison was the 27-year-old co-founder of Nottingham’s DiY sound system, so-called house music anarchists, who were known for throwing joyful free parties in fields and forests, quarries and squats. Now those gatherings could be criminalised and, for the first time, the music he played was being legally codified as “sounds wholly or predominantly characterised by the emission of a succession of repetitive beats”. “It was almost like a surrealist prank,” he says now. “I said: ‘Is this real?’ It was a crazy mixture of the sinister and the absurd.”

The 179-page bill was a hotchpotch of measures, from updating obscenity law and lowering the age of consent for gay men to restricting the right to silence when arrested and enabling the collection of DNA samples. Andrew Puddephatt, then director of the civil rights group Liberty, calls it “a Christmas tree bill. You bung a lot of different issues into one big bill as a way of securing parliamentary time.” At the time, Puddephatt described it as “the most wide-ranging attack on human rights in the UK in recent years”.