Introduction

Project Structure

Stack Diagram

Docker images

Django image

Nginx image

Redis image

Docker Compose

Environment Variables

The file

Deploying

Building

Deploying with Docker Compose

After many iterations, this is my current process to deploy a django application.

The cool thing is that I’m now deploying with only an .env file and nothing else.

Note that this is just a single instance of the stack, without Kubernetes or any kind of load balancer.

Introduction

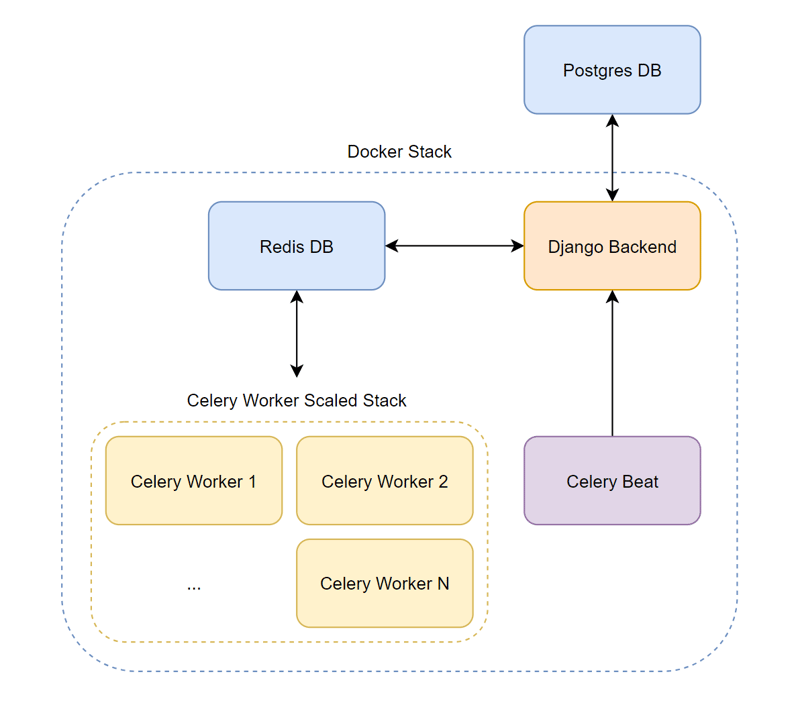

My stack consists on:

A Postgres database

A Redis database

A django instance

Celery beat and workers

I won’t go into details of how to set up anything like this here, if you want to learn more about celery in their docs.

Project Structure

To understand the docker-compose.yml file below, it’s important to see how I structure my django project:

├── core # settings.py lives here

├── app1/

│ ├── migrations

│ ├── models.py

│ └── …

├── app2/

│ ├── migrations

│ ├── models.py

│ └── …

├── data # A data directory where I store stuff like logs

├── nginx/

│ ├── certs/

│ │ ├── fullchain.pem

│ │ └── privkey.pem

│ ├── conf/

│ │ ├── default.conf

│ │ ├── prod.conf

│ │ └── staging.conf

│ └── Dockerfile

├── Dockerfile

├── entrypoint-django.sh

├── entrypoint-beat.sh

├── entrypoint-worker.sh

├── Pipfile

└── …

Stack Diagram

To visualize the flow better here’s a diagram that describes how everything is interconnected:

Docker images

The stack, though it might seem complicated, is only composed of 3 images, 2 of which are custom:

Django image

This is a custom image built from python.

This image will be used for django, celery workers and celery beat containers.

Here’s the Dockerfile for it:

# I use bullseye because I’m more comfortable with it

# but you can use Alpine for a more lightweight container

FROM python:3.11-bullseye

# Exposes port 8000

# Make sure to change this to your used port

EXPOSE 8000

# Keeps Python from generating .pyc files in the container

ENV PYTHONDONTWRITEBYTECODE=1

# Turns off buffering for easier container logging

ENV PYTHONUNBUFFERED=1

# Working directory

WORKDIR /app/backend

# Install pipenv

# This is not necessary if you use pip in your code

RUN pip install -U pipenv

# Install pipenv requirements

# Turns the Pipfile to a requirements.txt

# so it can be installed globally with pip

COPY Pipfile Pipfile.lock /app/backend/

RUN pipenv requirements > requirements.txt

RUN pip install -r requirements.txt

RUN rm -rf ./Pipfile ./Pipfile.lock

# Copy all the code over

COPY . .

# Create the media directory

RUN mkdir -p /app/backend/media

# Create a volume for the media directory

VOLUME /app/backend/media

# Create a volume for the static directory

VOLUME /app/backend/django_static

# Make the entrypoint scripts executable

# There’s one entrypoint for each service that uses this image

RUN chmod +x /app/backend/entrypoint-django.sh

RUN chmod +x /app/backend/entrypoint-worker.sh

RUN chmod +x /app/backend/entrypoint-beat.sh

# Set the default entrypoint in case this Dockerfile is run

# by itself

ENTRYPOINT [“/app/backend/entrypoint-django.sh”]

These are the entry point files for each service:

django entry point

# Migrate any new migrations to the database on deployment

echo “Migrating…”

python manage.py migrate –no-input

# Collect static files

echo “Collecting static files…”

python manage.py collectstatic –no-input

# Ensure the data directory exists

# I use the data directory to store files such as logs

mkdir -p data

# Start gunicorn

echo “Starting server…”

gunicorn core.wsgi:application –forwarded-allow-ips=“*” –bind 0.0.0.0:8000

Worker entry point

# Wait until the backend directory is created

until cd /app/backend

do

echo “Waiting for server volume…”

done

# run a worker

# I like having only one task per worker but you can change it

# by increasing the concurrency

echo “Starting celery worker…”

celery -A core worker -l info –concurrency 1 -E

Beat entry point

# Wait until the server volume is available

until cd /app/backend

do

echo “Waiting for server volume…”

done

# run celery beat

echo “Starting celery beat…”

celery -A core beat -l info

Nginx image

This container serves the application.

I create a custom nginx image that includes my certificates and configuration, so I don’t have to copy them over to the server.

Note: I don’t use certbot, as I find it more straightfoward to generate the certificates from cloudflare and just store them in the custom image

This means that the image should be secure in a private registry with authentication, otherwise you risk security of your web app.

Here’s the Dockerfile for it:

# Export ports 80 and 443

EXPOSE 80

EXPOSE 443

# Copy the nginx configuration files to the image

COPY ./conf/default.conf /etc/nginx/conf.d/default.conf

COPY ./conf/prod.conf /etc/nginx/conf.d/prod.conf

COPY ./conf/staging.conf /etc/nginx/conf.d/staging.conf

# Copy the CloudFlare Origin CA certificate to the image

COPY ./certs/fullchain.pem /etc/nginx/certs/fullchain.pem

COPY ./certs/privkey.pem /etc/nginx/certs/privkey.pem

Redis image

I just use the default Redis image for this.

Just want to note that, because this is a single instance deployment, I like deploying Redis directly here as I find it’s enough.

It is recommended, though, to spin up a Redis database somewhere more centralized.

Docker Compose

Environment Variables

Before I get into the gist of the Docker Compose file here are some environment variables I put in my .env file for deployment:

DOCKER_REGISTRY: My private, authentication enabled, docker registry where I upload the build images

DJANGO_DOCKER_IMAGE: The name I give the django image

NGINX_DOCKER_IMAGE: The name I give the NGINX image

DOCKER_TAG: Usually the version I want to deploy, i.e.: 1.5 or latest

The file

services:

redis:

container_name: redis

restart: unless-stopped

image: redis:7.2.0-alpine

expose:

– 6379

backend:

restart: unless-stopped

image: ${DOCKER_REGISTRY}/${DJANGO_DOCKER_IMAGE}:${DOCKER_TAG}

env_file:

– ./.env

entrypoint: /app/backend/entrypoint-django.sh

ports:

– 8000:8000

volumes:

– ./data:/app/backend/data

healthcheck:

test: [“CMD”, “curl”, “-f”, “http://localhost:8000/healthcheck/”]

interval: 30s

timeout: 10s

retries: 3

start_period: 20s

worker:

restart: unless-stopped

image: ${DOCKER_REGISTRY}/${DJANGO_DOCKER_IMAGE}:${DOCKER_TAG}

env_file:

– ./.env

entrypoint: /app/backend/entrypoint-worker.sh

volumes:

– ./data:/app/backend/data

depends_on:

backend

condition: service_healthy

redis

condition: service_started

beat:

restart: unless-stopped

image: ${DOCKER_REGISTRY}/${DJANGO_DOCKER_IMAGE}:${DOCKER_TAG}

env_file:

– ./.env

entrypoint: /app/backend/entrypoint-beat.sh

volumes:

– ./data:/app/backend/data

depends_on:

backend

condition: service_healthy

redis

condition: service_started

nginx:

restart: unless-stopped

image: ${DOCKER_REGISTRY}/${NGINX_DOCKER_IMAGE}:${DOCKER_TAG}

ports:

– 80:80

– 443:443

depends_on:

backend

condition: service_healthy

As you can see, the compose file has the 5 services, Redis, django, celery worker, celery beat and NGINX.

Deploying

Building

First I build the images and push them to the registry. Before, I did this manually, now I use a GitHub action. You can learn more about this automation here.

Deploying with Docker Compose

Then I head to the server where I want to deploy this. Make sure that the .env file is updated and then just:

docker compose down: Spin the old instance down

docker system prune -a -f: This makes sure I remove the latest image to force the download of the new one from the registry.

docker compose up –scale worker=5 -d: Spin the new instance up

That’s it!